Recently, there has been much fanfare in the media in Vietnam about the rising position of Vietnamese education in international rankings. The e-newspaper of the Vietnam Association of Colleges and Universities, the VNExpress e-newspaper, the Voice of Vietnam, and many others all point to different sources to testify and document the achievements that Vietnam has made.

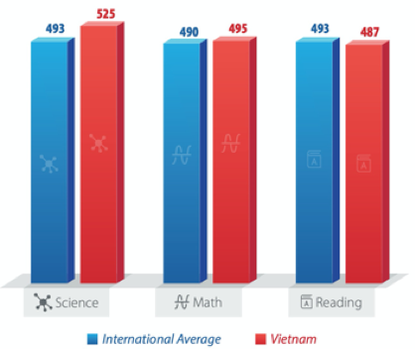

Participating for the first time in PISA in 2012, Vietnam’s 15-year-olds performed on par with their peers in world-renowned Germany and Austria (OECD, 2012), and then on par with Australia in 2015 (FactsMaps, 2015). Although an official ranking of Vietnam is yet to be published for 2018, the country test scores were amazingly high.

Fig. 1 PISA score of Vietnamese students and International Average in 2018 (EVBN, 2018)

At the International Mathematics and Science Olympiad (IMSO) 14 in 2017, the Vietnam team of 12 students won 12 medals. Vietnamese students also won gold medals from the World Invention Creativity Olympic taking place in South Korea in 2019.

The Global Innovation Index (GII)[1] had Vietnam at 71, 59, 47, 45, and 42 for 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively. The same index ranked Vietnam at 18 out of 126 countries for 2018 in terms of innovation in education (Global Innovation Index).

Apparently, Vietnamese education is surfacing in the international arena. And yet, behind the scenes there is always the shadow of the trophy: there is only a loose link between education outputs and social demands in Vietnam.

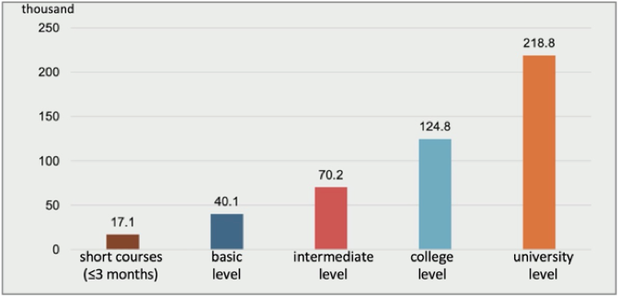

The Report on Vocational Education 2016 by the National Institution for Vocational Education and Training of Vietnam revealed a hard fact: the higher education levels, the higher the rates of unemployment.

Fig. 2: Number of unemployed people aged 15-60 by vocational training background. (National Institution for Vocational Education and Training, 2016)

The Voice of Vietnam e-newspaper remarked that tertiary programmes are not realistic, are heavily test-based, and result in low levels of transfer. Therefore, they are limited in career orientation. (VoV, 2018).

According to the World Bank, the quality of Vietnamese human resources ranks 11th out of 12 surveyed countries in Asia. Of 53.4 million labourers aged 15+, only 49% have had training. This is more evident at advanced levels where there is a bigger lack of skilled workers and technical workers (Tap chi Mat tran 2019).

The mismatch of education outputs and social demands can be attributed to several factors. Among them are heavily-academic programme contents, and misconception of the employment-guaranteeing value of university degrees.

High school and university curricula still rely heavily on theoretical lessons and knowledge input, without sufficient practical working knowledge or skills, placing knowledge before competence. In this model, knowledge is both the input of the education training process and the expected output.

Classes, whether at high schools or higher education institutions, are in most places conducted in the traditional way with the teacher as the preacher imparting knowledge to the students. Twenty-first century skills are thus mostly neglected. Decision-making is lacking. Problem-solving is not taught, experienced or trained for. People-skills are not practised. Little is known of global citizenship.

Most of what students are expected to do is absorb the knowledge from the teacher, recite what has been taught, and do exercises that have little real-life value. Higher education programmes are loosely connected to the actual demands of the society. According to Professor Le Huu Lap, this is due to the weak connection between colleges, universities and business entities. This has led to two parallel lines of movement, with higher education institutions on one track, and the business sector on the other. They both advance, but do not seem to meet each other.

The second factor is the over-emphasis on the value of a university degree. In the belief that this is the passport to a good job, perceived generally as one that brings a high

salary, coupled with the hope that their children will become leaders, not workers, parents push their children to the limit to gain access to higher education. This has resulted in an imbalance of demand and supply where a lack of technical workers and skilled workers prevails in the industry, and a surplus of university graduates look for jobs. As a result, many have to content themselves with a job totally unrelated to their degree major.

However, a paradigm shift is already taking place.

In November 2013, the Communist Party of Vietnam released the Resolution “On fundamental and comprehensive renovation of education and training” to meet the demands of developing high-quality human resources, building a knowledge economy in the process of industrialization and modernization, and the development of a socialist-oriented market economy and international integration.

To realise this ambition, Vietnam has reserved the quite high portion of over 20% of the national budget for education. In terms of GDP and education, the expenditure-to-GDP ratio topped ASEAN member countries in three successive years from 2017 to 2019, spending 5.7% of its GDP for education (Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO, 2017, 2018, 2019).

Since the release of the Resolution, efforts have been made at national, provincial and local levels to implement it. Radical schools in cities and major provincial places of the country have been experimenting with task-based lessons, theme-based workshops, and problem-solving activities, with promising results to date.

Starting in 2020, the country is going to implement the new primary and secondary education curriculum, which is intended to help develop students’ ability to solve problems and achieve task objectives via theme-based activities that put knowledge into practice. Several universities have taken into consideration social demands in developing their programmes.

The country is undergoing an education renovation towards a more open system of education where transferability between formal and continuing education is made possible. In the wake of the surplus of academic graduates, it is promoting a paradigm shift from academic dominance to vocational prevalence, flipping the current 70/30 ratio of academic to professional-vocational student bodies for an expected 30/70 ratio.

To conclude, it is worth quoting Jean Piaget, “The principal goal of education in the schools should be creating men and women who are capable of doing NEW [emphasis added] things, not simply repeating what other generations have done”. Similarly, William Arthur Ward said that “Teaching is more than imparting knowledge, it is inspiring change. Learning is more than absorbing facts, it is acquiring understanding.” In light of these statements, Vietnam appears to be moving in the right direction.

References

Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO. (2017). The Global Innovation Index 2017: Innovation Feeding the World, Ithaca, Fontainebleau, and Geneva. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2017.pdf.

Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO. (2018). The Global Innovation Index 2018: Energizing the World with Innovation. Ithaca, Fontainebleau, and Geneva. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2018.pdf.

Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO. (2019). The Global Innovation Index 2019: Creating Healthy Lives—The Future of Medical Innovation, Ithaca, Fontainebleau, and Geneva. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2019.pdf.

EVBN. (2018). Education in Vietnam. Research report. http://www.ukabc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/EVBN-Report-Education-Final-Report.pdf

FactsMaps. (2015). PISA 2015 Worldwide Ranking – average score of math, science and reading. http://factsmaps.com/pisa-worldwide-ranking-average-score-of-math-science-reading/)

Global Innovation Index. Available at: https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/home.

Le Huu Lap. (2018). “Đào tạo nguồn nhân lực: Lạc điệu xa rời thực tiễn”. https://saigondautu.com.vn/kinh-te/dao-tao-nguon-nhan-luc-lac-dieu-xa-roi-thuc-tien-53926.html.

National Institution for Vocational Education and Training. (2016). National Report on Vocational Education and Training. Youth Publishing House. Hanoi.

OECD. (2012). PISA 2012 Results in Focus. What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know. Tap chi Mat tran. (2019). Thúc đẩy liên kết trường đại học và doanh nghiệp ở nước ta trước bối cảnh cách mạng công nghiệp lần thứ tư. http://tapchimattran.vn/thuc-tien/thuc-day-lien-ket-truong-dai-hoc-va-doanh-nghiep-o-nuoc-ta-truoc-boi-canh-cach-mang-cong-nghiep-lan-thu-tu-22218.html.

VoV. (2018). Đào tạo đại học còn xa thực tế. https://vov.vn/xa-hoi/giao-duc/dao-tao-dai-hoc-con-xa-thuc-te-nang-ne-thi-cu-814447.vov.